Rare complication “portique” clock, Pillard in Troyes

Price on request

In stock

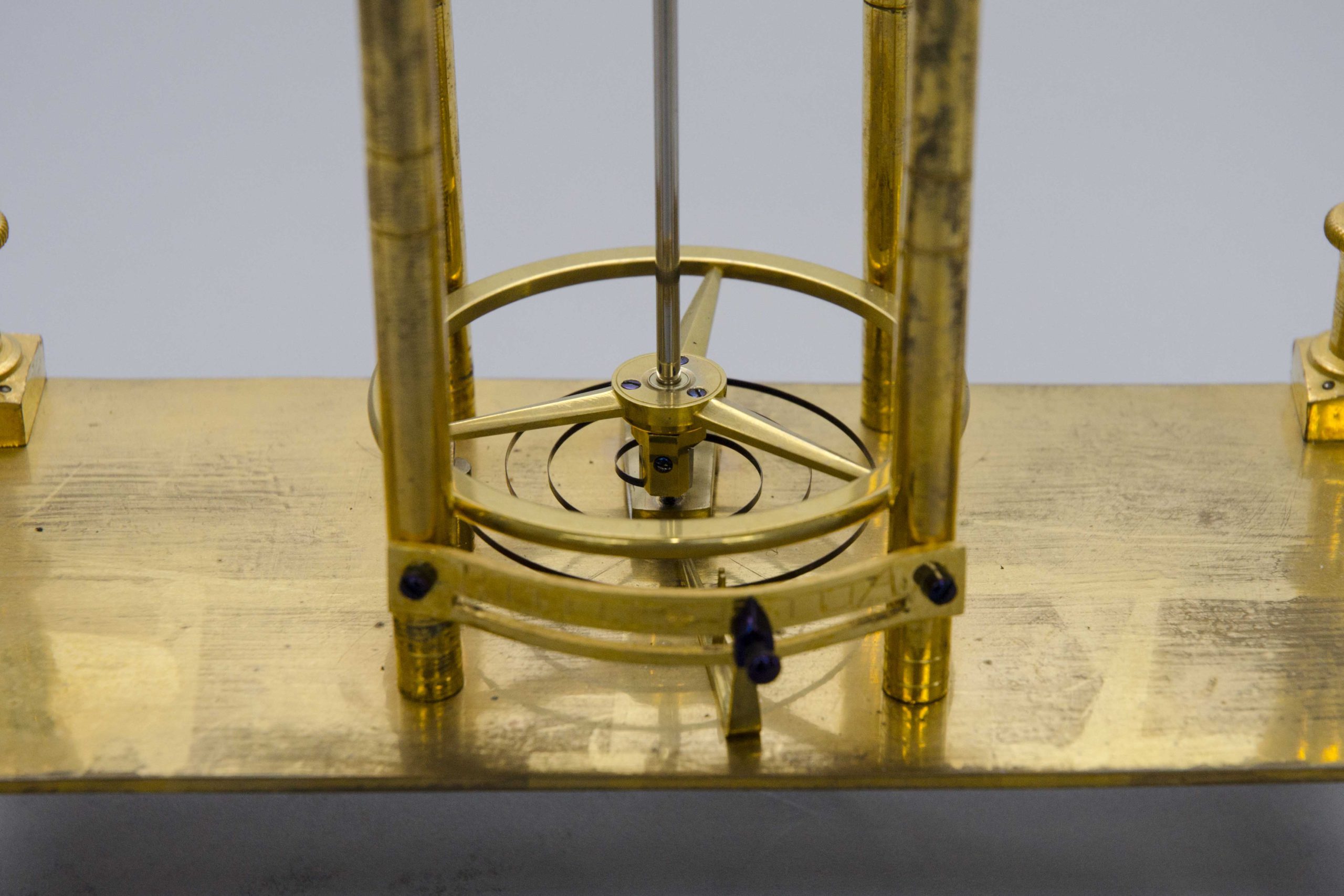

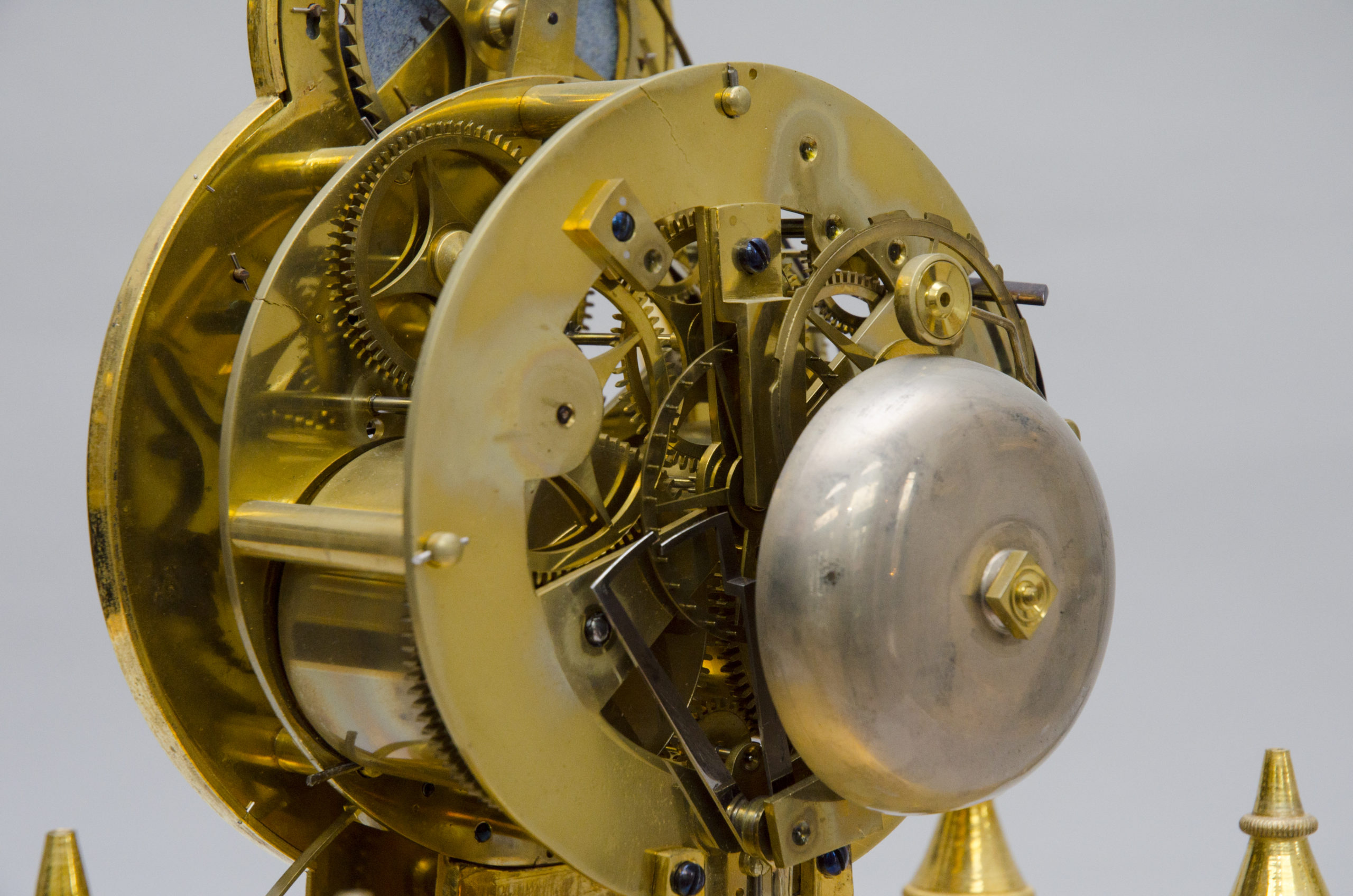

Contact usVery rare four-dial skeleton clock with complication, portico signed by the clockmaker Pillard in Troyes on the enamelled central dial with Roman and Arabic numerals. Ring balance, pin escapement and central second hand. Upper moon phase dial and two small lower dials. Signed Pillard à Troyes on the enamle made and signed on the back by the most famous enameller of the time “Coteau, rue poupée N°7”.

Size: H 41cm x W 20cm

Last quarter of the 18th century, signed under the central dail for the clockmaker Pillard in Troyes (France).

Carefully cleaned by our master clockmaker (dismantling, cleaning, reassembly, oiling), this masterpiece is in perfect working order!

Lith: Joseph Coteau (1740–1801) was the most famous enameller of his time and collaborated with most of the great Parisian watchmakers of the period. He was born in Geneva, where he became a master painter-enameller at the Académie de Saint Luc in 1766, before moving to Paris a few years later. From 1772 until the end of his life, he lived on Rue Poupée.

Coteau does not seem to have enamelled watches or small pieces, but rather specialised in larger works, which were technically more complex due to shrinkage during firing. A document from Sèvres indicates that he and Parpette (who also worked at the factory) introduced gold leaf enamelling (a technique that involved using enamelled gold leaf) on soft and hard porcelain. Coteau also experimented with various polychromes, producing a blue that was so rare and difficult to perfect that few of his contemporaries were able to copy it. The enamel paint was applied with a brush to a copper plate, then the different colours were vitrified one by one in the kiln. The decoration was then enhanced with gilding, which, after firing, gave a matt finish. This was then polished to restore its metallic sheen. He subsequently used this technique to decorate the dials of his most precious clocks.

The particularity of the skeleton clock is to let see its mechanism on the reverse and through its openwork dial. Heir to the gantry clock, it is usually composed of an arch supporting one or more dials. This form was a great success in the last years of the eighteenth century and into the first half of the nineteenth century because of the desire of watchmakers to demonstrate their mastery, technical progress, as well as in response to the decorative overload of figurative clocks.

In stock

Contact us