In 1295, with Marco Polo’s return to Venice, Europeans discovered the refinement of Chinese porcelain with wonder and envy. In 1498, with the discovery of the India route by Vasco da Gama, the Portuguese became the first importers of Chinese porcelain into Europe.

The craze for these ceramics of unparalleled finesse and translucency continued to grow in all European courts. A wind of challenge blew through these courts: who would be the first to discover the secret of the Chinese craftsmen? To which prince would the honour and benefits of the discovery of porcelain accrue?

A paragraph on the website of the KPM Berlin factory sums up the importance of porcelain and the secret of its manufacture in 18th-century Europe for the men and women of the 21st century:

“In 1717, Augustus the Strong sent 600 Saxon horsemen to Frederick William I, King of Prussia, in exchange for 151 pieces of porcelain from the Charlottenburg and Oranienburg palaces. From then on, the market value of the porcelain was fixed: Four men on horseback are worth one vase!

That says it all!

It is true that the Medici had already succeeded in producing a few objects in their Florentine workshop in the 16th century, but it was not until 1710 in Saxony and the discovery of Johann Friedrich Böttger (1682-1719), a brilliant chemist who was a prisoner of his ruler Augustus the Strong, that a more significant production appeared. This was the birth of Meissen porcelain!

Il est vrai que les Medici avaient déjà réussi au 16e siècle à produire quelques objets dans leur atelier florentin, mais il faudra attendre l’an 1710 en Saxe et la découverte de Johann Friedrich Böttger (1682-1719), chimiste de génie prisonnier de son souverain Auguste le Fort, pour voir apparaitre une production plus importante. C’est la naissance de la porcelaine de Meissen!

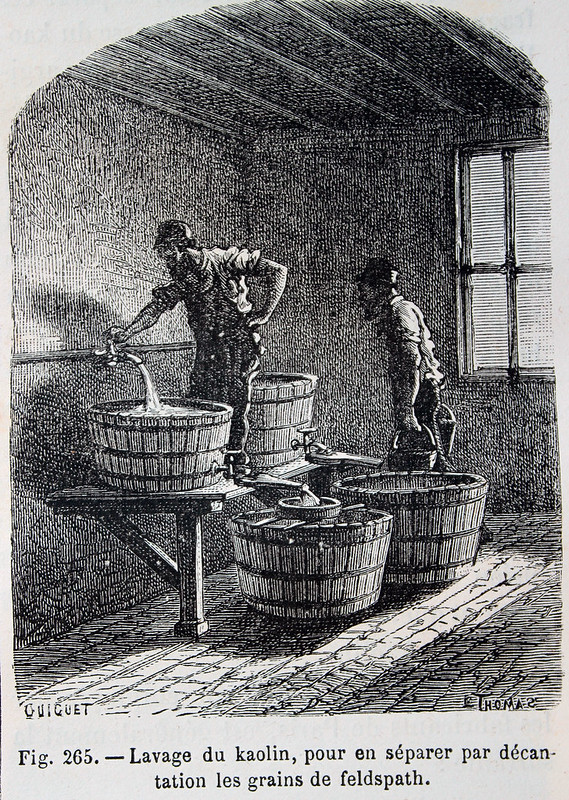

The secret is Kaolin! A white refractory clay which, when mixed with quartz and feldspath and fired at more than 1,200 °C, makes the porcelain white, very resistant and translucent.

Luckily, the Germans found it in their own soil. The French waited until 1768-1769 to discover a white powder in the region of Limoges, in Saint-Yrieix-la-Perche to be precise, which women used to clean their wash! The curse was finally lifted, as France became able to produce its own porcelain without the constraints of expensive and hazardous kaolin imports. This marked the end of soft-paste porcelain production, except at Sèvres where it was still produced until 1804.

Nevertheless, this soft paste porcelain, milky white, scratchable and produced without kaolin, is highly appreciated and sought after by today’s collectors. The value of these rare objects continues to rise.

Aurélie Di Egidio

L’Egide Antiques in Brussels, the 20th of August 2021

Source :

- Faïence et porcelaine de Paris, 18e et 19e siècle, Régine de Plinval de Guillebon, éditions Faton. 1995.

- www.kpmberlin.com

- Limoges, deux siècles de porcelaine, Chantal Meslin-Perrier et Marie Segonds-Perrier, les éditions de l’Amateur, 2002.

- Meissen ou l’invention de la porcelaine européenne, Dossier de l’art n°174, mai 2010, p 94-95 par Caillaud-de Guido Laurence.